Tensor product

Related: tensor algebra.

Sean $E$ y $F$ dos $K$-espacios vectoriales de dimensión finita:

Se define el espacio vectorial $E\otimes F$ como el espacio vectorial generado por los símbolos $\{e\otimes f ,e \in E, f\in F\}$ junto con las relaciones

$$ (ae+bf)\otimes (a'e'+b'f')= $$ $$ =aa'e\otimes e'+ab'e\otimes f'+ba'f\otimes e'+bb'f\otimes f' $$The elements of a tensor product are called tensors. See intuition behind tensors.

They are usually used to construct tensor fields.

Examples: energy-momentum tensor, Cauchy stress tensor, ...

Esta definición encierra la idea de la bilinealidad pero desde un punto de vista dual, es decir, sobre los "objetos", no sobre las aplicaciones. Ello se aprecia en la siguiente proposición.

Proposition

$Bil(E,F;K)=(E \otimes F)^*$

$\blacksquare$

Y la siguiente consigue que quede todo más compacto y elegante:

Proposition

$(E \otimes F)^*=E^* \otimes F^*$

$\blacksquare$

Es decir, que $E^* \otimes F^*$ es una forma de interpretar las aplicaciones bilineales de dos espacios vectoriales de manera separada.

Por otra parte, si tenemos aplicaciones lineales de $E$ con coeficientes en $K$ y queremos ampliar los coeficientes utilizamos el producto tensorial:

Proposition

It is satisfied that

$$ E^* \otimes F=\mathcal{L}(E,F) \tag{1} $$$\blacksquare$

Dado un espacio vectorial $E$, se definen los tensores de tipo $(r,s)$ como los elementos del espacio vectorial $E^*\otimes \stackrel{s}{...} \otimes E^*\otimes E\otimes \stackrel{r}{...} \otimes E$, que se pueden interpretar como aplicaciones

$$ T:E\times \stackrel{s}{...} \times E \to E\otimes \stackrel{r}{...} \otimes E $$como se deduce de la proposición anterior.

También podemos interpretar al tensor $T$ como una forma multilineal:

$$ T: E\times \stackrel{s}{...} \times E\times E^*\times \stackrel{r}{...} \times E^* \to \mathbb{R} $$(OJO AL CAMBIO DE PAPELES DE r y s!!!)

Los tensores generalizan a las matrices en el siguiente sentido:

- Una aplicación lineal hacia $\mathbb{R}$ desde un espacio $E$ es un elemento de $E^*$ y al mismo tiempo una matriz "unidimensional" (matriz fila).

- Una aplicación bilineal hacia $\mathbb{R}$ desde $E$ es un elemento de $E^* \otimes E^*$ y al mismo tiempo una matriz de "dimensión 2" (las de toda la vida): dada $f \in Bil(E,E;K)$, y fijando una base $\{e_i\}$ de $E$, tenemos la matriz $A=(f(e_i,e_j))$. Es un cálculo sencillo comprobar que para $v,w\in E$, $f(v,w)= (v1, \dots, v_n) \cdot A \cdot (w1, \dots, w_n)^t$

- Una aplicación trilineal será al mismo tiempo un elemento de $E^* \otimes E^* \otimes E^*$ y un "objeto" tridimensional, como una matriz pero de dimensión 3.

- Etcétera...

Pero no solo modelizan formas multilineales, sino cualquier aplicación multilineal de s copias de E en r copias de E, como se ha dicho más arriba. Veámoslo con un ejemplo concreto.

Consideremos un tensor $T$ de tipo (1,2). Esto significa que es un elemento de $E^*\otimes E^* \otimes E$. Por (1) tenemos que $T$ se puede interpretar como una aplicación lineal de $E \times E$ en $E$.

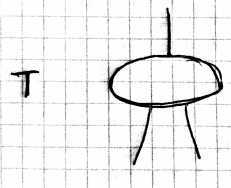

Según la Penrose abstract index notation diríamos que $T$ es $T_{ab}^c$ y con la Penrose diagramatic notation sería:

Kronecker product

If we have two linear maps between vector spaces: $S : V \rightarrow X$ and $T : W \rightarrow Y$, we can define a new linear map on the tensor product of the domains

$$ S \otimes T : V \otimes W \rightarrow X \otimes Y $$by means of the expression

$$ (S \otimes T)(v \otimes w)=S(v) \otimes T(w) $$The matrix of this map (respect to the corresponding basis) is called the Kronecker product of the matrices

$$ \left[ \begin{array}{ll}{a_{1,1}} & {a_{1,2}} \\ {a_{2,1}} & {a_{2,2}}\end{array}\right] \otimes \left[ \begin{array}{ll}{b_{1,1}} & {b_{1,2}} \\ {b_{2,1}} & {b_{2,2}}\end{array}\right]= $$ $$ =\left[ \begin{array}{cc}{a_{1,1} \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{b_{1,1}} & {b_{1,2}} \\ {b_{2,1}} & {b_{2,2}}\end{array}\right] \quad a_{1,2} \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{b_{1,1}} & {b_{1,2}} \\ {b_{2,1}} & {b_{2,2}}\end{array}\right]} \\ {a_{2,1} \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{b_{1,1}} & {b_{1,2}} \\ {b_{2,1}} & {b_{2,2}}\end{array}\right] \quad a_{2,2} \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{b_{1,1}} & {b_{1,2}} \\ {b_{2,1}} & {b_{2,2}}\end{array}\right]}\end{array}\right]= $$ $$ =\left[ \begin{array}{llll}{a_{1,1} b_{1,1}} & {a_{1,1} b_{1,2}} & {a_{1,2} b_{1,1}} & {a_{1,2} b_{1,2}} \\ {a_{1,1} b_{2,1}} & {a_{1,1} b_{2,2}} & {a_{1,2} b_{2,1}} & {a_{1,2} b_{2,2}} \\ {a_{2,1} b_{1,1}} & {a_{2,1} b_{1,2}} & {a_{2,2} b_{1,1}} & {a_{2,2} b_{1,2}} \\ {a_{2,1} b_{2,1}} & {a_{2,1} b_{2,2}} & {a_{2,2} b_{2,1}} & {a_{2,2} b_{2,2}}\end{array}\right] $$Quantum mechanics

It is important the use of the tensor product in Quantum Mechanics. I think it appears when you have observables that are "totally independent" (in a sense that I must formalize), for example, $x$ position and $y$ position (maybe "commuting observables" is the correct name). It let us "expand" the set of possibilities. It is the counterpart of cartesian product. See On Physics from the beginning .

Another approach: the tensor product plays a crucial role in describing composite quantum systems. (Or a system with commuting observables, I think. For example $x$-position and $y$-position.)

The tensor product is an operation that takes two vector spaces (in this case, the state spaces of the two individual quantum systems) and produces a new vector space (the state space of the composite system). This new space has dimensions that are the product of the dimensions of the original spaces.

In the case of two qubits, each qubit has a state space of dimension 2 (with a basis usually chosen as {|0>, |1>}). When you take the tensor product of these two spaces, you get a new state space of dimension 4 (with a basis usually chosen as {|0,0>, |0,1>, |1,0>, |1,1>}).

Entangled states are those that cannot be written as a tensor product of states of the individual systems. In other words, an entangled state is a state of the composite system that cannot be simply described in terms of the states of its constituent parts.

Better example: particle with position and spin.

________________________________________

________________________________________

________________________________________

Author of the notes: Antonio J. Pan-Collantes

INDEX: